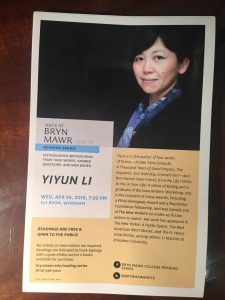

I recently attended the final event of this year’s Reading Series, a visit from author Yiyun Li. Li is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the recipient of numerous prestigious awards, and the author of a memoir, three novels, and two short fiction collections.

I first came to know of Li through her short stories such as “All Will Be Well” and “A Flawless Silence,” which tend to focus on women who vacillate between participants and outsiders to normal society. They guard complex secrets. On the surface they perform their expected roles, while internally they harbor forbidden dreams and angers. When I picked up Li’s novel “Kinder than Solitude,” I found a more sprawling and philosophical style, but similar concerns. The three protagonists of “Kinder than Solitude” grew up together in Beijing, but became estranged after a mutual friend was mysteriously poisoned. Nobody can agree who was at fault for the terrible event, but it seems clear that it was not an accident. This might seem like the set-up for a thriller or mystery, but Li approaches the subject with the same measured grace as her short stories. Decades after the rupture, the two female protagonists are expatriates in the United States. Much like the women in Li’s short stories, they live on the margins of the normal. Moran, once a loving child, is now unable to form deep attachments or put down roots. The odd, calculating Ruyu prefers to linger in the background of any social circle. Boyang, the male protagonist, has remained in Beijing and become wealthy, but he is no less lonely than his former friends. The trio seeks and rejects companionship, each of them painfully strategic in the revelation of their true selves.

During Li’s talk in the Ely Room, she began by reading a section from her new novel, “Where Reasons End,” a conversation between a mother and her deceased son. She then read a haunting excerpt from her novella “Kindness.” Finally, Li read us her story “A Sheltered Woman.” At various moments humorous, wry, and then heart-wrenching, this story is about a nanny who, against her will and better judgement, is drawn into the dysfunctional life of her newest employer.

As always, there was a Q and A session after the reading. Li veered away from trite answers. In response to a question about her inspiration, Li said that while she doesn’t “use” her acquaintances as characters, she does draw from certain life experiences in order to process them and understand them better. She stated, “Fiction is a way of understanding things that don’t make sense…The story has to injure you in a way, or else it’s just a story.” Another audience member asked Li to speak about her experiences as a Chinese-American writer, to which she demurred, wondering if she could be better classified as an Irish writer or a Russian writer based on the literary lineage of her work.

I surprised myself by raising my hand at the end to ask a question of my own. After Li had mentioned that she found it difficult to share personal details about her life in nonfiction, I found myself wondering if that was related to her cast of fictional characters as well. I asked Li to speak about it, and was thrilled by her answer. After a moment’s thought, she said, “Characters lie to us. They don’t want us to know their real stories. It is a writer’s job to push them.” She described silence and secrets as being the source of great pressure which can be alleviated through narrative, as if the writer takes the lid off of a character’s life.

In regards to the negotiation between her reticent characters and the surveillance of their societies: “My characters all have secret lives because they cannot have live privately, whether in China or America. It is the writer’s job to reveal that secret life.”