Field trips were one of the most exciting parts of my early school years. Getting to leave school during the middle of the day and bringing bagged lunches onto the bus were just the beginning of the adventure. Going to museums, theaters, and nature centers broke up our normal routine and got us learning in completely new ways. Field trips in college accomplish much the same function—and their infrequency makes them all the more novel.

Field trips were one of the most exciting parts of my early school years. Getting to leave school during the middle of the day and bringing bagged lunches onto the bus were just the beginning of the adventure. Going to museums, theaters, and nature centers broke up our normal routine and got us learning in completely new ways. Field trips in college accomplish much the same function—and their infrequency makes them all the more novel.

A few weeks ago my class “Latin American and Latino Art and the Question of the Masses,” traveled together to Taller Puertoriqueño, a Latino arts and cultural center in the Fairhill neighborhood of northeast Philadelphia. Along with Professor Martín Gaspar, six of my classmates and I left the campus on a snowy morning to see the exhibit “The Complicit Eye,” presented to us personally by the artist Kukuli Velarde. In an artist’s statement, Velarde writes: “I am a Peruvian-American artist. My work, which revolves around the consequences of colonization in Latin American contemporary culture, is a visual investigation about aesthetics, cultural survival, and inheritance. I focus on Latin American history, particularly that of Perú, because it is the reality with which I am familiar. I do so, convinced that its complexity has universal characteristics and any conclusion can be understood beyond the frame of its uniqueness.” Once we arrived at Taller, Velarde led us around the stunning exhibition, stopping to discuss the inspiration and thought-process behind each of the pieces. Her paintings are large-scale and impressive, incorporating a vast artistic language with influences ranging from 1940s pin-up style to the colonial Catholic tradition of the Cuzco School. Velarde told us, however, that she never starts a painting with the intention to communicate a political message. Rather, she focuses on the personal and aesthetic meaning of the piece. Nonetheless, political meaning seeps into her art, and despite the deeply individual subject matter, Velarde’s body often seems to act as a placeholder for larger communities.

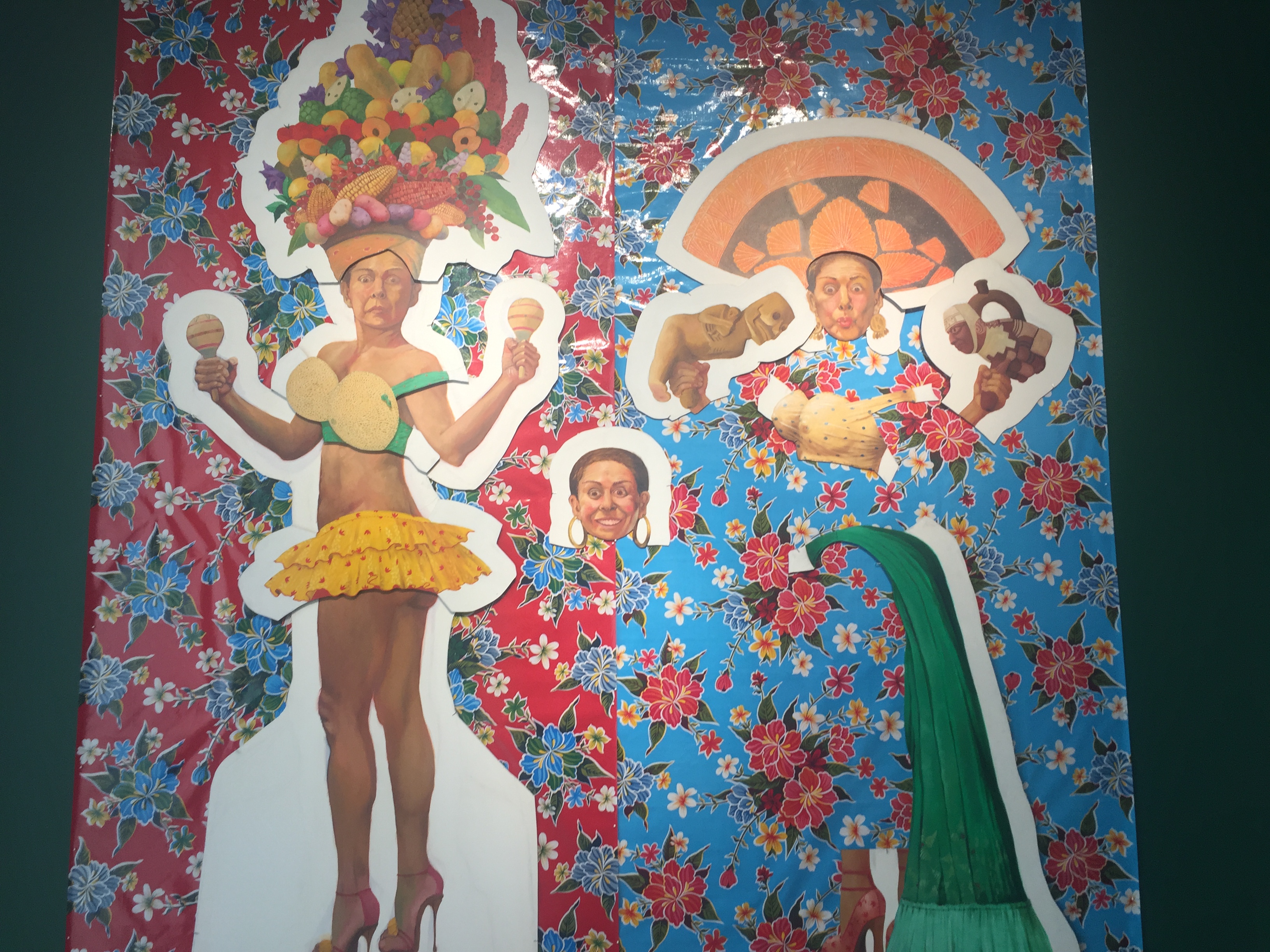

Once we arrived at Taller, Velarde led us around the stunning exhibition, stopping to discuss the inspiration and thought-process behind each of the pieces. Her paintings are large-scale and impressive, incorporating a vast artistic language with influences ranging from 1940s pin-up style to the colonial Catholic tradition of the Cuzco School. Velarde told us, however, that she never starts a painting with the intention to communicate a political message. Rather, she focuses on the personal and aesthetic meaning of the piece. Nonetheless, political meaning seeps into her art, and despite the deeply individual subject matter, Velarde’s body often seems to act as a placeholder for larger communities. In “Hispanic Ready Made,” for example, Velarde depicts stereotypes of Latin American women superimposed onto her own body. The caricatured images, from a headpiece made of tropical fruits to sexualized outfits, mock the grotesque nature of stereotypes. Velarde said that she detests the word “Hispanic,” believing it to reflect a homogenization of diverse experiences. She would rather delve into the specifics of heritage and ethnicity, avoiding generalizations by referring to herself simply as Peruvian.

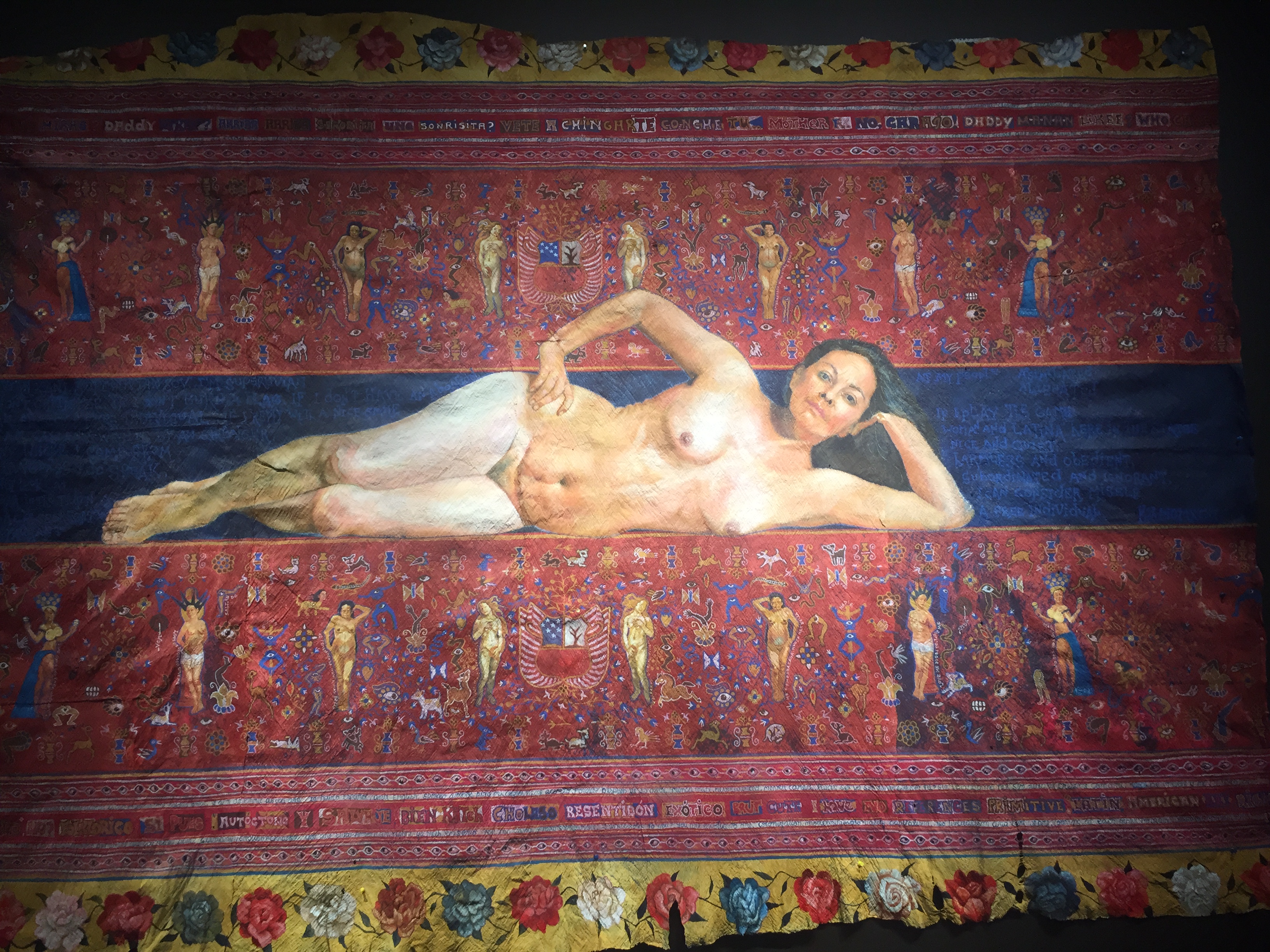

In “Hispanic Ready Made,” for example, Velarde depicts stereotypes of Latin American women superimposed onto her own body. The caricatured images, from a headpiece made of tropical fruits to sexualized outfits, mock the grotesque nature of stereotypes. Velarde said that she detests the word “Hispanic,” believing it to reflect a homogenization of diverse experiences. She would rather delve into the specifics of heritage and ethnicity, avoiding generalizations by referring to herself simply as Peruvian. Many of the paintings are depictions of a specifically female agony. “Love Me Diosito, Love Me” responds to what Velarde described as a cultural glorification of women’s suffering. “Yo Misma Soy” is an earlier self-portrait that shows Velarde exposed for the viewer’s inspection (Both of these can be found on Velarde’s website here). Velarde spoke about her art as a way to take possession of the humiliation and objectification that she has experienced as a woman. Her paintings allow her to take control of her own image, reversing and confronting society’s voyeuristic gaze. Even when decapitated, crucified, and stabbed, the steady and challenging eyes of Velarde’s subjects tell the viewer, I know what you’ve done and I know what you think of me.

Many of the paintings are depictions of a specifically female agony. “Love Me Diosito, Love Me” responds to what Velarde described as a cultural glorification of women’s suffering. “Yo Misma Soy” is an earlier self-portrait that shows Velarde exposed for the viewer’s inspection (Both of these can be found on Velarde’s website here). Velarde spoke about her art as a way to take possession of the humiliation and objectification that she has experienced as a woman. Her paintings allow her to take control of her own image, reversing and confronting society’s voyeuristic gaze. Even when decapitated, crucified, and stabbed, the steady and challenging eyes of Velarde’s subjects tell the viewer, I know what you’ve done and I know what you think of me.  “The Complicit Eye” is a gorgeous and haunting exhibit, and can be seen through April. Velarde is also constructing a mural, which we saw partially completed, and should be interesting to see again later on in the exhibition period. I was also disappointed by the difference between seeing the paintings in person and looking at the photos I took. I definitely was not able to capture their technical detail or precision, so I recommend taking a trip to Taller Puertorriqueño and seeing them yourself!

“The Complicit Eye” is a gorgeous and haunting exhibit, and can be seen through April. Velarde is also constructing a mural, which we saw partially completed, and should be interesting to see again later on in the exhibition period. I was also disappointed by the difference between seeing the paintings in person and looking at the photos I took. I definitely was not able to capture their technical detail or precision, so I recommend taking a trip to Taller Puertorriqueño and seeing them yourself!