On a recent Wednesday morning, I stopped by Bryn Mawr’s Special Collections to look at some materials from the Ellery Yale Wood Collection of Children’s Books. The Ellery Yale Wood Collection was donated to the college in 2016 and includes around 12,000 books, with materials spanning from the 18th to the 20th centuries. I was hoping that the collection would help me with a project for my Transatlantic Childhoods class, which is taught by Professor Chloe Flower, English department’s brand new specialist in children’s literature and culture. Working with such rare primary materials is a wonderful opportunity, but this was actually the first time I visited Special Collections outside of a class.

On a recent Wednesday morning, I stopped by Bryn Mawr’s Special Collections to look at some materials from the Ellery Yale Wood Collection of Children’s Books. The Ellery Yale Wood Collection was donated to the college in 2016 and includes around 12,000 books, with materials spanning from the 18th to the 20th centuries. I was hoping that the collection would help me with a project for my Transatlantic Childhoods class, which is taught by Professor Chloe Flower, English department’s brand new specialist in children’s literature and culture. Working with such rare primary materials is a wonderful opportunity, but this was actually the first time I visited Special Collections outside of a class.

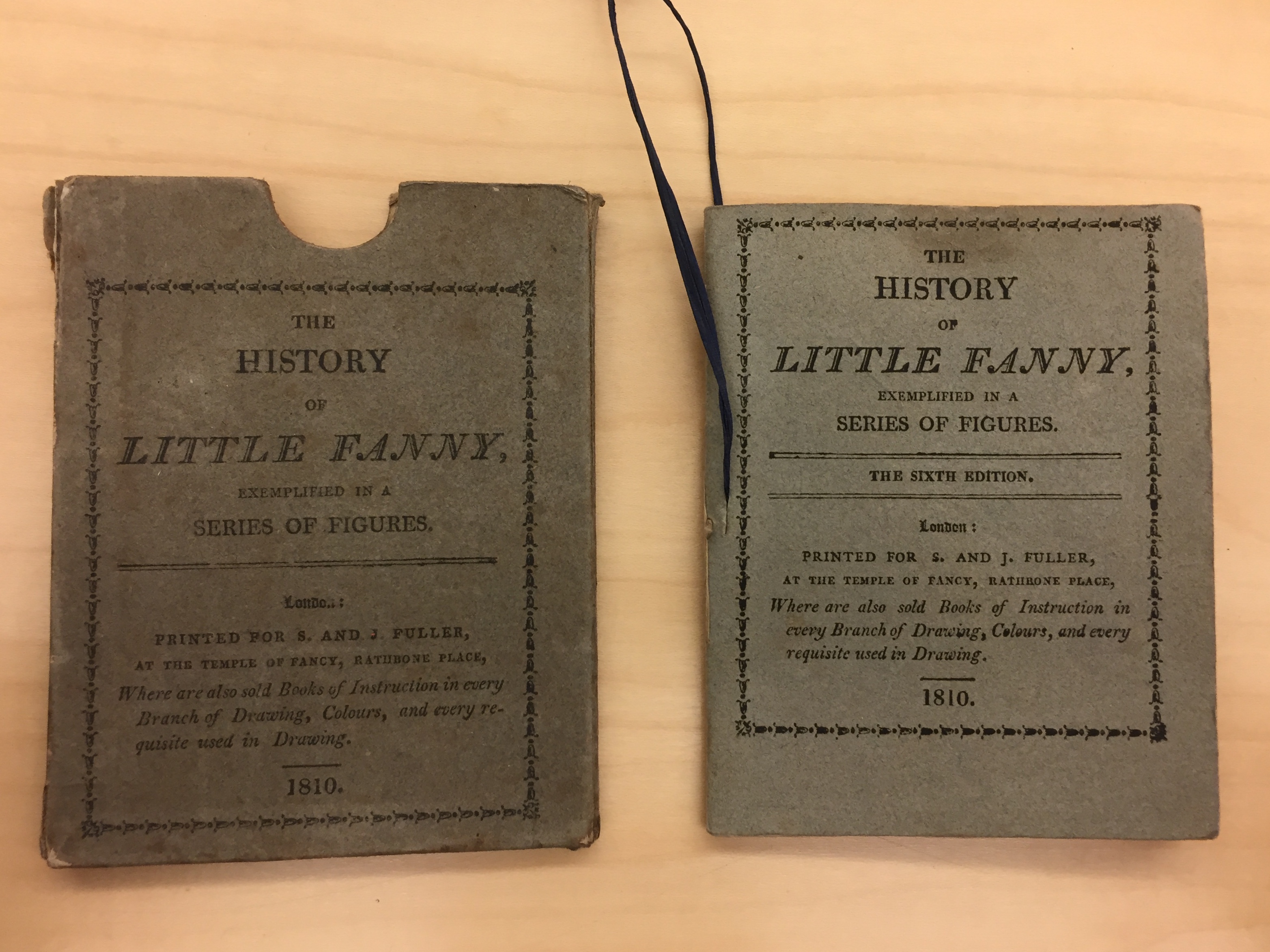

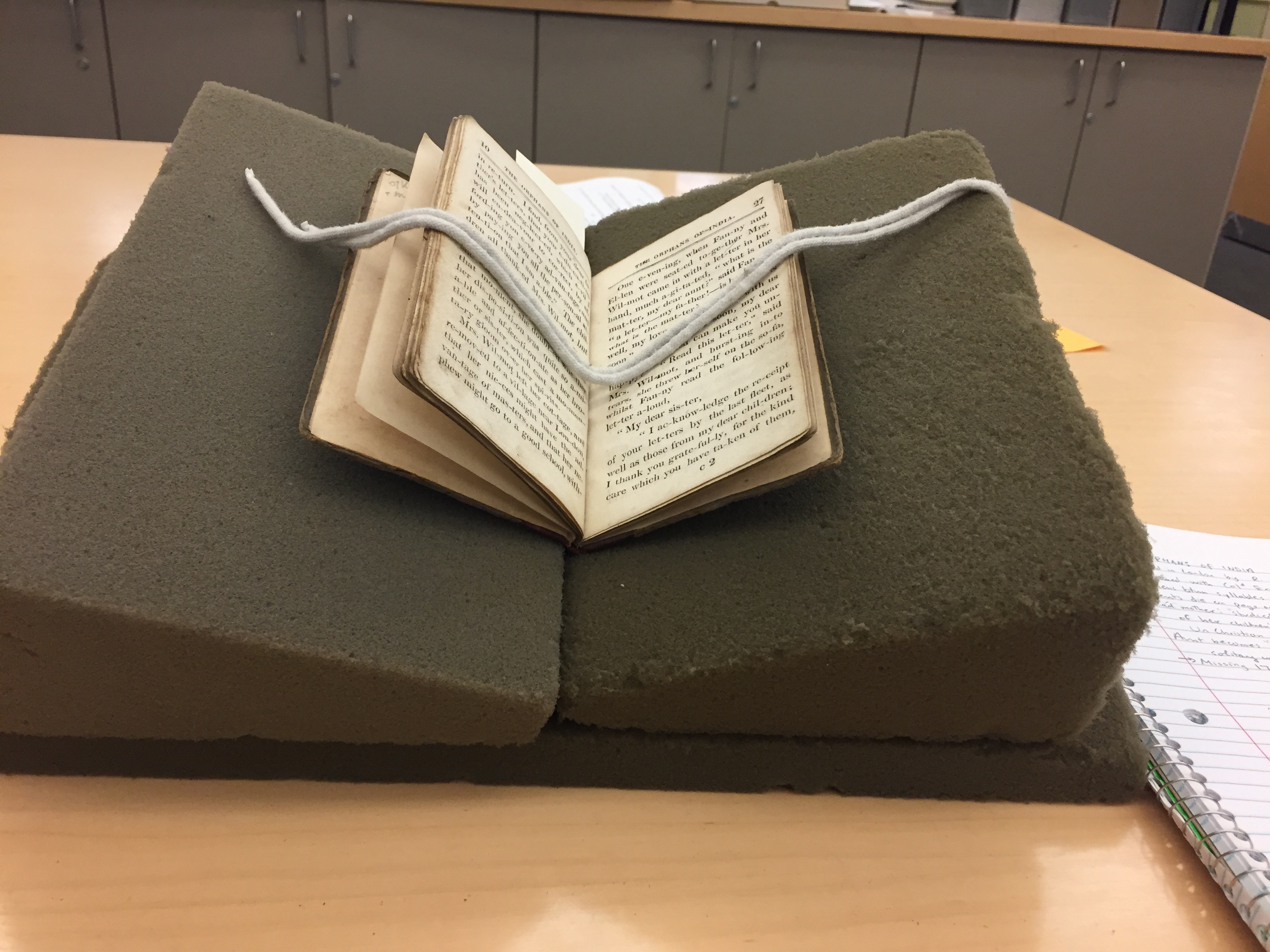

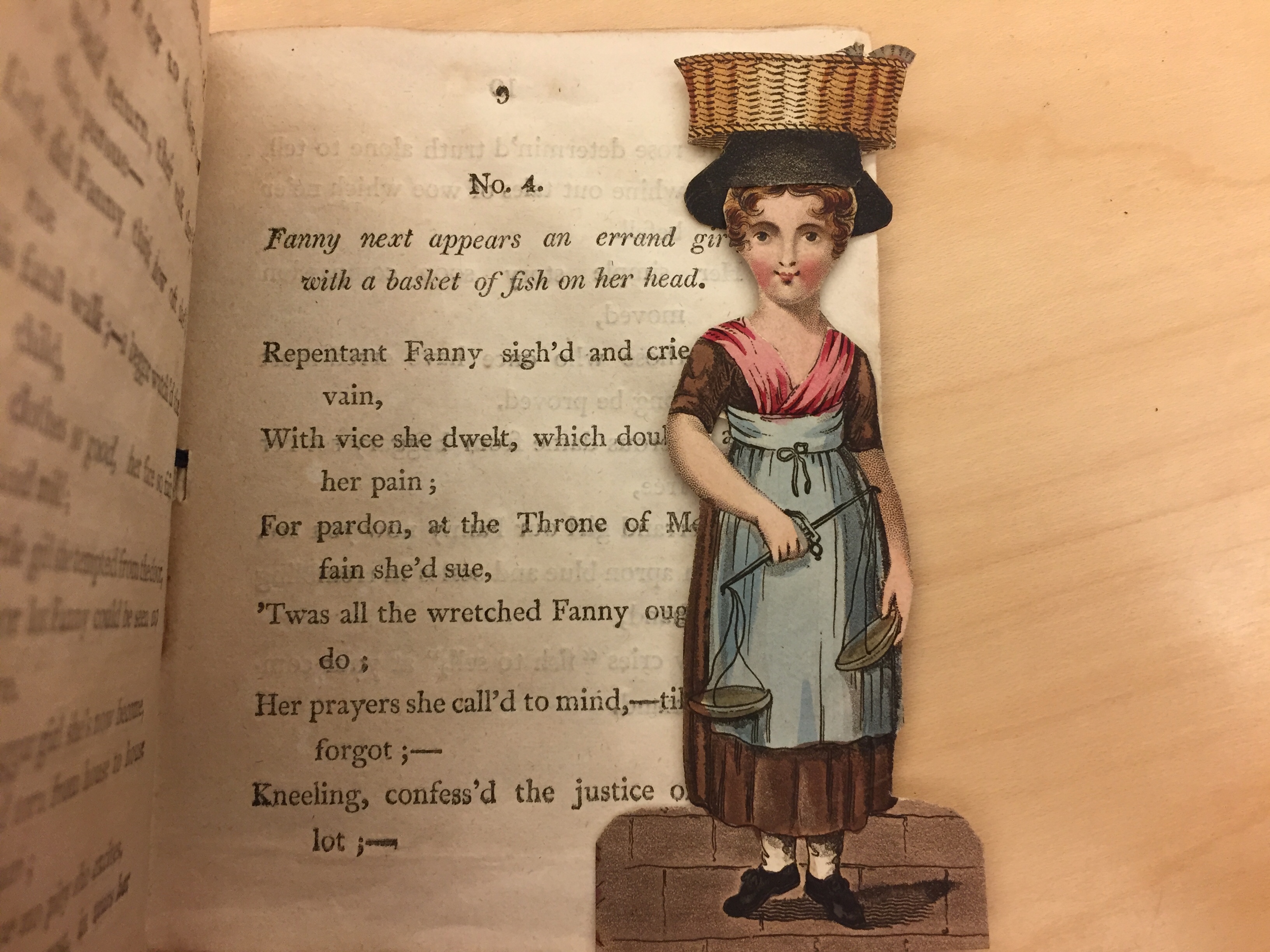

I looked at two texts, The Orphans of India: a Tale for Young People, and The History of Little Fanny, published in 1815 and 1810 respectively. Both of these little books have survived remarkably. Although brittle, the pages are intact (with the exception of 17 pages from the middle of The Orphans of India; sadly I’ll never know the full details of the fates of the orphans in question). Nonetheless, the materials are fragile enough that it’s best to look at them on foam supports, with weighted cords to hold them in place.

In class we’ve been reading and discussing a wide variety of American and British genres such as poetry, pedagogical texts, picture books, and novels. I became interested in the recurring theme of orphans. In modern children’s books, orphanhood is often romanticized: conveniently absent parents allow for greater independence and adventuring. By contrast, in texts from the 19th century, orphanhood seems to be held up as a threat. Children who are disobedient or ungrateful are punished with abandonment, a fear which is based in the historical reality of widespread child labor and cultural anxieties about delinquency.

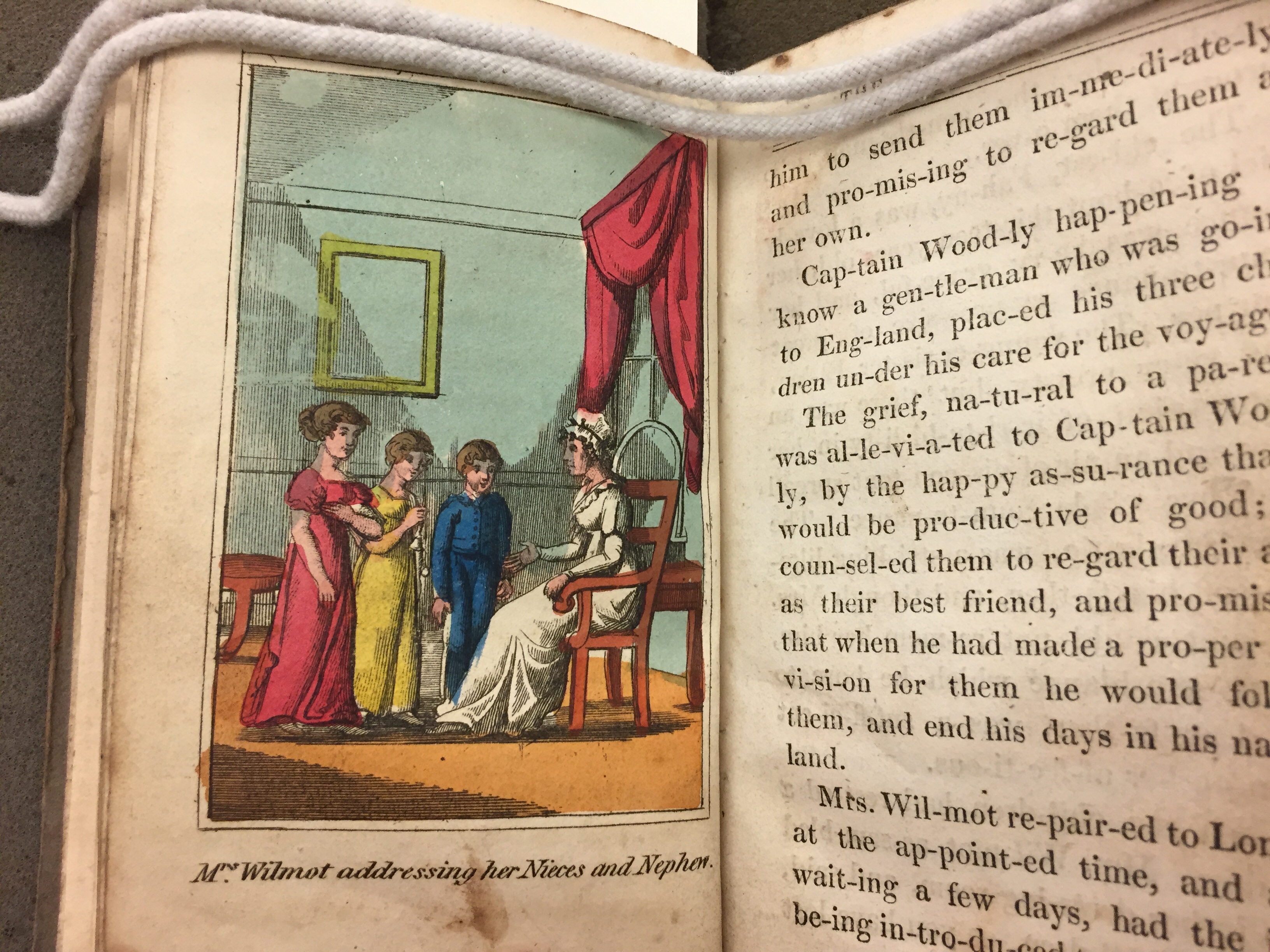

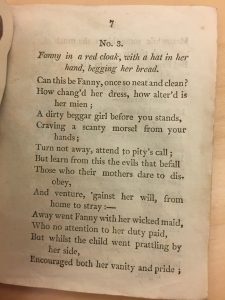

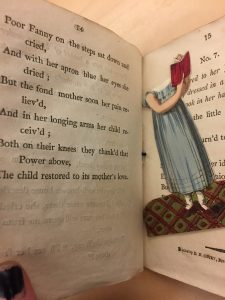

The Orphans of India and Little Fanny share an instructive purpose; the characters who, through their own faults, become orphans, serve as examples to the reader. These books were written to teach children literacy, but they also work to maintain a social order, hinting that a disruption of the status quo would mean not just a breakdown of society, but of the most basic sources of childhood stability. In The Orphans of India, a girl named Ellen tells a petty lie that causes the deaths of her father, aunt and brother. In Little Fanny, Fanny’s mother tells her not to stray from home, and when Fanny disobeys, she ends up a homeless beggar. She is re-accepted by her mother once she learns to be “pious, modest, diligent, and mild.”

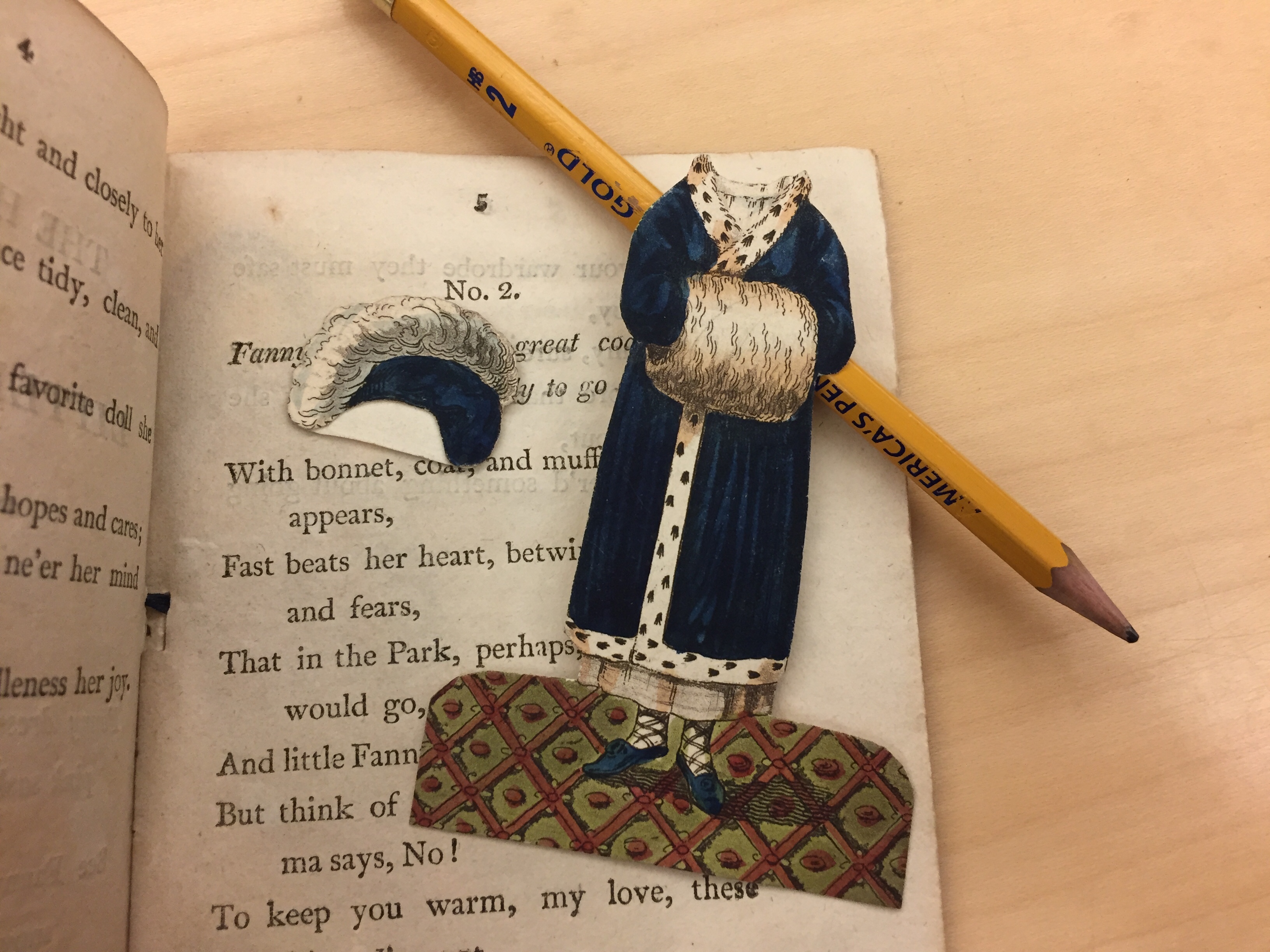

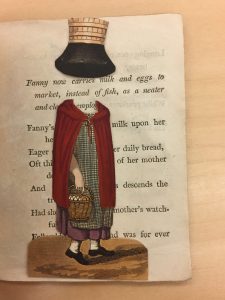

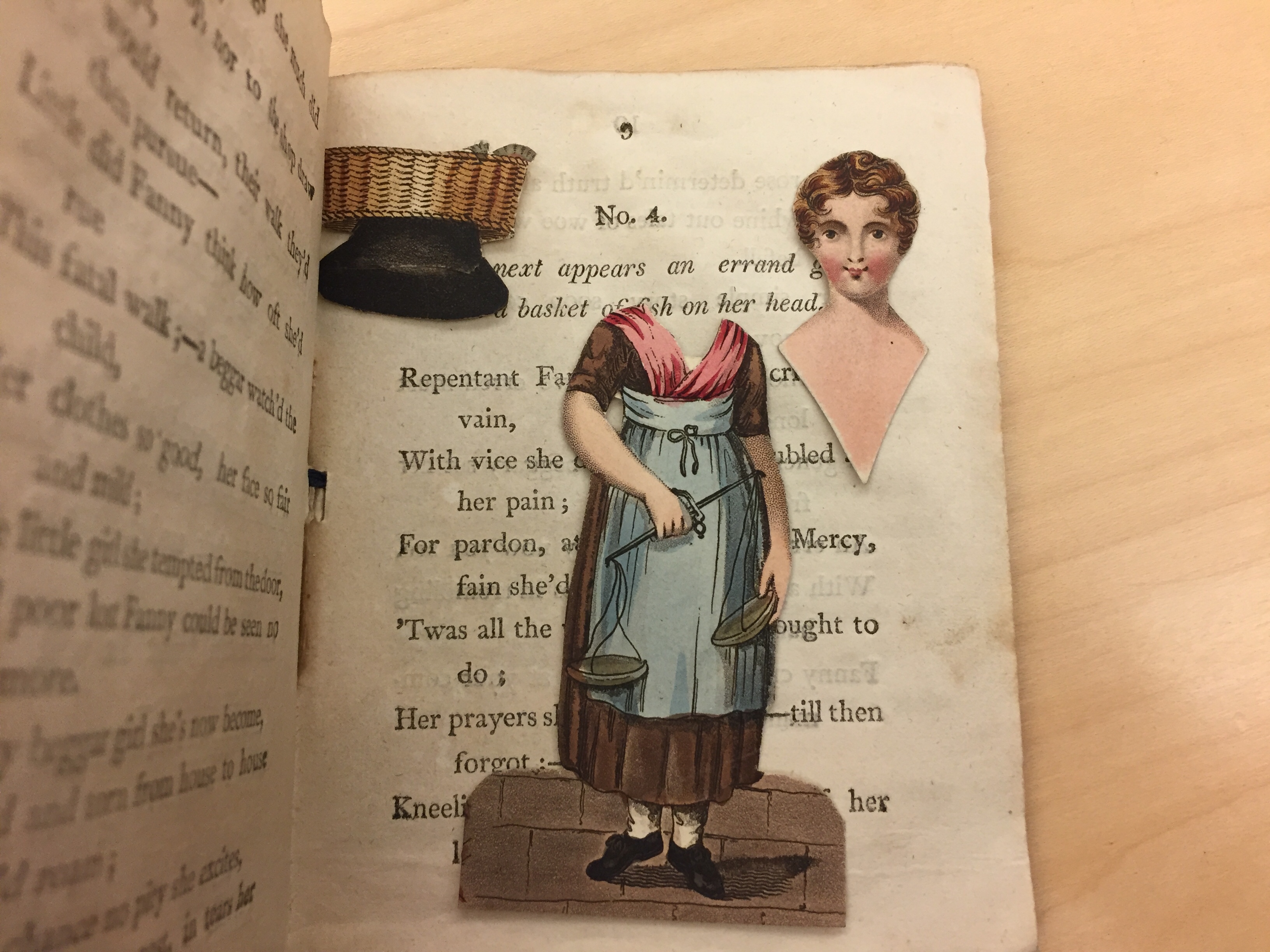

Handling original copies of historical books adds a richness and context to the texts. The History of Little Fanny, for example, came with paper dolls that correspond to the various phases of the narrative. Fanny has a new outfit for each scene, complete with little accessories like a feathered hat when she is a pampered rich girl, and a basket of eggs to carry in her lowered status as an errand girl. These pieces of material culture reinforce the text, and perhaps helped a very young child to internalize its message.

Read more about the Ellery Yale Wood Collection here: http://bulletin.brynmawr.edu/features/once-upon-a-time/