This fall, Bryn Mawr is exhibiting four of the five interactive art installations that make up ear-whispered: Works by Tania El Khoury. Tania El Khoury is an artist who works in London and Beirut. She partnered with Bryn Mawr as a part of the 2018 Fringe Festival. In September, I was able to see two of El Khoury’s pieces, Camp Pause and Gardens Speak. I wanted to write a little bit about my experiences with these installations, but it’s been difficult to decide what I wanted to say.

Camp Pause is a video installation that can be viewed all semester in Canaday Library. It pieces together the narratives of four Palestinian residents of the Rashidieh Refugee Camp in Lebanon. Various storytelling threads come together in Camp Pause to create an unsettling but powerful impact. When you walk in, there are four screens facing each other, all playing simultaneously through headphones; while you can only concentrate on one story at a time, you are aware of the others going on at the same time. Some visual elements appear in more than one of the videos, hinting at common threads among residents of the camp. The ocean is a strong motif in all of the stories. It makes up one of the camp’s borders—the other being a military checkpoint—and therefore represents the refugees’ feelings of entrapment and claustrophobia. At the same time, the videos’ subjects often feel drawn to the water, entranced by the beauty and mystery of the natural world.

It’s hard to draw a clear moral from Camp Pause. Pieces of the camp’s historical background are interspersed with the often gut-wrenching stories of the camp’s residents. The one that struck me the most followed a young girl, because of the normalcy with which she viewed her life in the camp. In fact, her biggest complaint about her community was the abundance of litter by the seaside. It made me wonder how the generation that is growing up in Rashidieh will come to understand their situation.

Gardens Speak was only open for a limited length of time at Bryn Mawr. The piece was inspired by people who were killed by the regime in Syria. Their families are forbidden from holding public funerals, so the martyrs are often buried in secret or private graves. Gardens Speak gathers these stories through interviews with survivors, and creates a really singular experience. Although it was entirely immersive installation, it was an experience for the senses of touch, smell, and hearing, rather than vision. This seemed quite unique for any piece of art, and I felt a bit apprehensive as the small group of us were ushered into the Hepburn Teaching Theater.

The space was entirely black, with only dim lighting. We were asked to leave our shoes and electronic devices at the entrance, and then we put on plastic coats over our clothes. Then we were led to the room, where we saw what looked like a plot of earth. Simple headstones stuck out of the soil, and each of us took our places at a different “grave.” Our guide had instructed us to begin digging in the dirt by our headstone; the dirt under my hands felt moist and smelled strongly of real vegetation. Soon enough, I found a sort of inflated cushion, from which a voice emanated. To hear, each of us had to lie down with our ears pressed against the speaker. The dirt was very uncomfortable under my body. I soon learned that the voice I was hearing was telling the story of Abdul Wahid al-Dandashi, as if in his own words. He told a brutal story of being tortured in an army prison, learning that his brother had been killed, and even after that, choosing to return to Syria and fight.

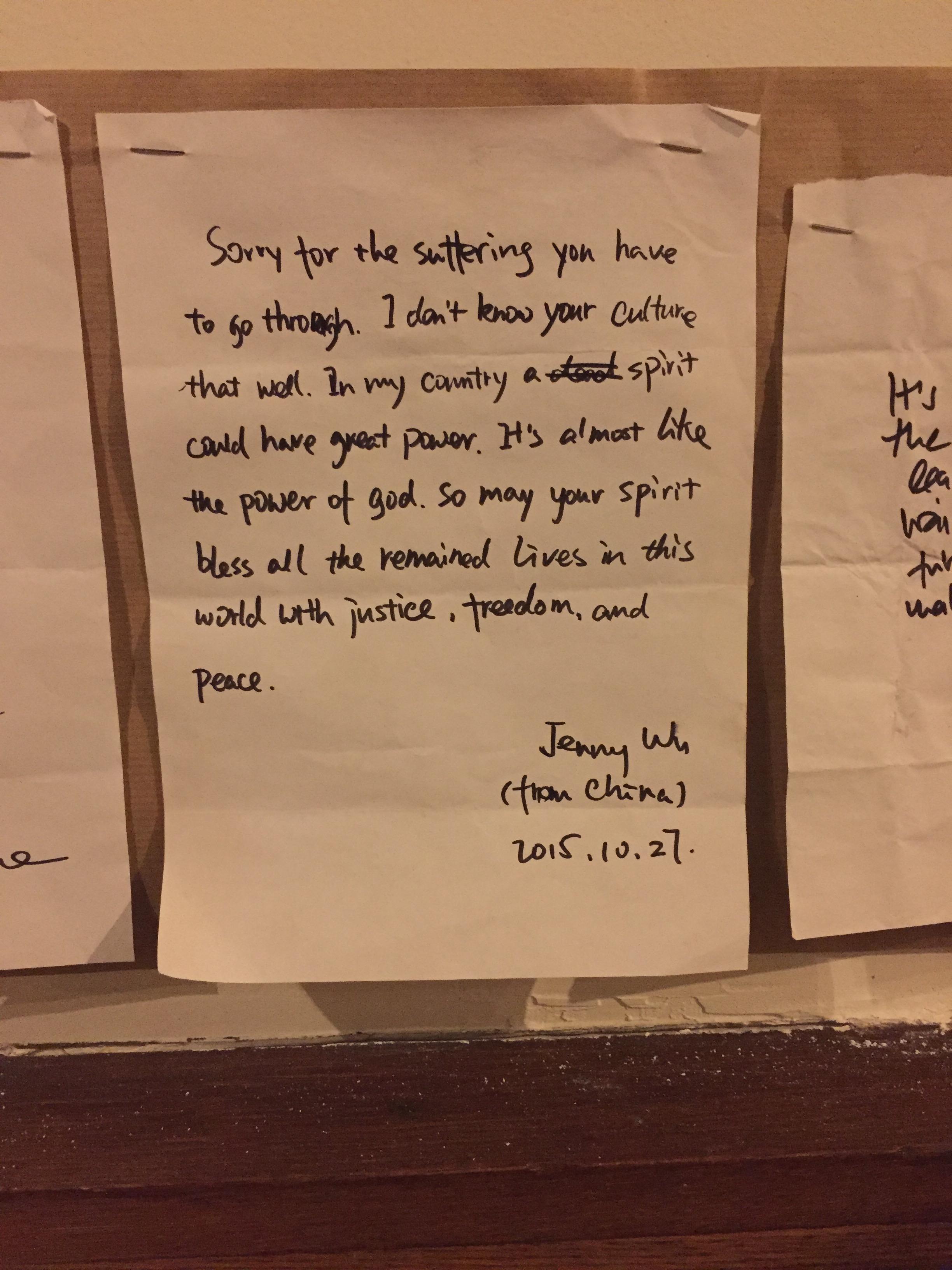

When each of the graves had finished speaking, all of us were invited to write a letter addressed to the person whose story we had heard, responding to the experience in any way. We then buried our letters back under the soil, where they would later be collected and added to the exhibit. As you can imagine, this was a sobering experience, and I found it interesting, once I had retrieved my shoes and washed the dirt off my hands, to go downstairs to see all the letters from past exhibitions displayed. Many of the letters—maybe even most of them—expressed a loss for words. Like Camp Pause, it’s hard to find an easy symbolism or moral to Gardens Speak. One might feel anguish over the senseless loss of life, or sympathy for someone whose loved one was killed, but what is there to say? “I’m sorry” is inadequate and feels detached, even meaningless. At the same time, it seems patently untrue to claim you can feel the pain of something so removed from your own life. Some of the letters I read expressed hopelessness, thinking of how many people could sacrifice their lives for freedom, yet still that dream is unrealized. The reaction that I most appreciated reading, which came from only a few letters, was inspiration. Some people, after seeing Gardens Speak, felt energized to dedicate their lives to a great cause, or to live for something truly worthwhile.

Letters written to Syrian martyrs, displayed in Goodhart Theater