Back at Bryn Mawr after a semester abroad, I’m daunted by the thought of returning to long days and nights in the library. I steel myself for the dozens of pages of reading for every class and the papers to be turned in with alarming regularity. In an effort to remind myself of what I love about academia, I stroll through the stacks of Canaday library. Getting lost among books written about subjects I know nothing about, I think of a passage from Sherman Alexie’s novel The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. Gordy, a boy from a rural and often closed-minded town, takes our protagonist Arnold to the meager-looking high school library.

“There are three thousand four hundred and twelve books here,” Gordy said. “I know that because I counted them.”

“Okay, now you’re officially a freak,” I said.

“Yes, it’s a small library. It’s a tiny one. But if you read one of these books a day, it would still take you almost ten years to finish.”

“What’s your point?”

“The world, even the smallest parts of it, is filled with things you don’t know.”

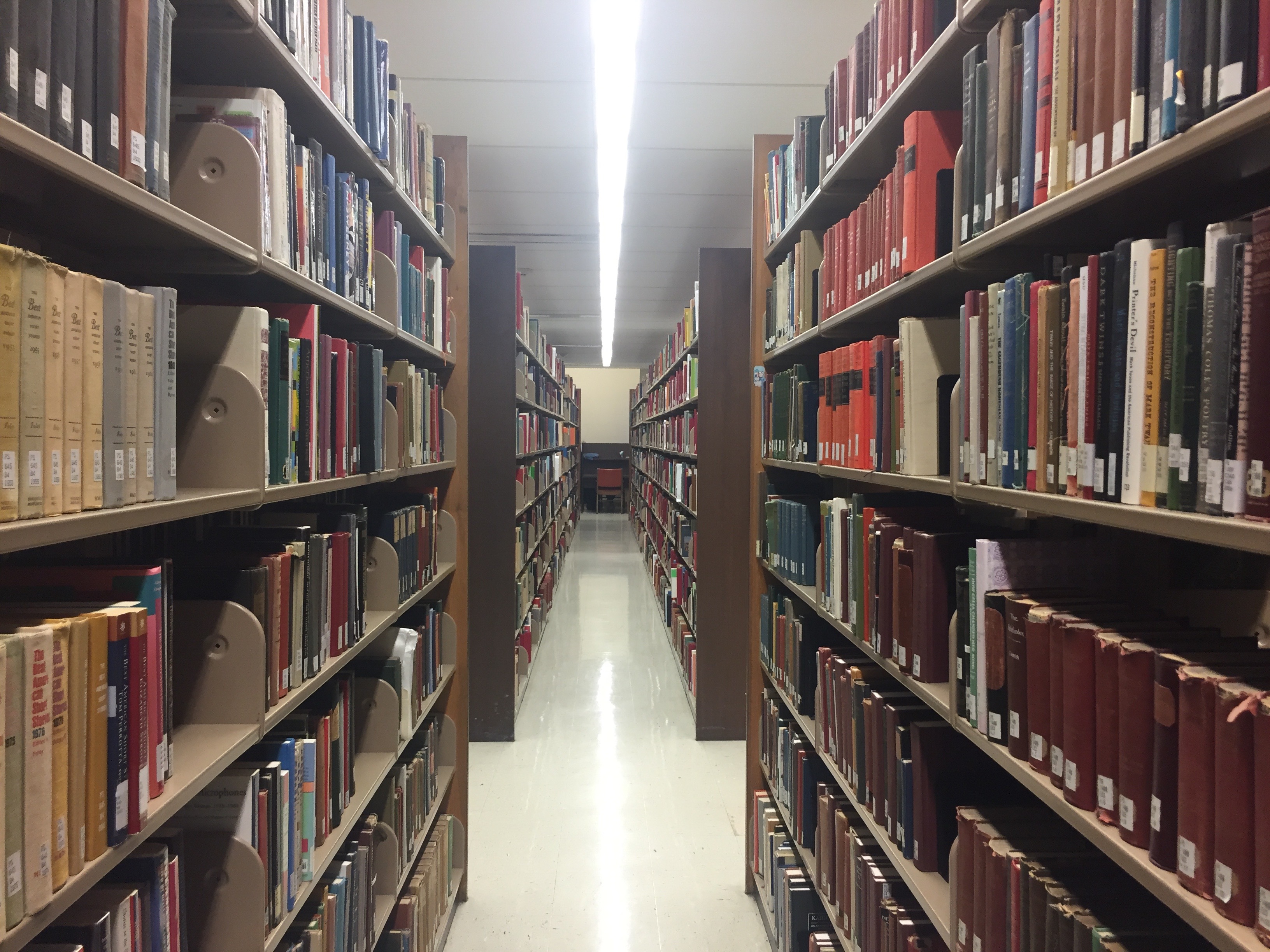

This idea sneaks into my life in various ways. When I was abroad, I realized that every new experience could be explored one step further, like one of those mesmerizing fractal images. You can’t understand a country without properly understanding a specific region, and then a specific town, and then by the time you even start to learn about the lives of even a few people who live there, you find yourself returning to the airport to go home. Bryn Mawr is a good place to keep uncovering mysteries. Even without attending a single class, you can tell that this is a place sodden with over a century of stories, artefacts brought from faraway places, staircases worn down by scholars’ incessant feet. And in the library, that kaleidoscope of knowledge becomes almost overwhelming. Sometimes I pull a book off the shelf at random, wondering when was the last time it was opened. I love the specificity of these titles, the obscurity. Poems by an author no one remembers. A history of a vanished kingdom. A book is meant to be used, but it is patient; it can wait indefinitely until someone needs it for just the exact piece of information, the perfect quote to round out an essay.

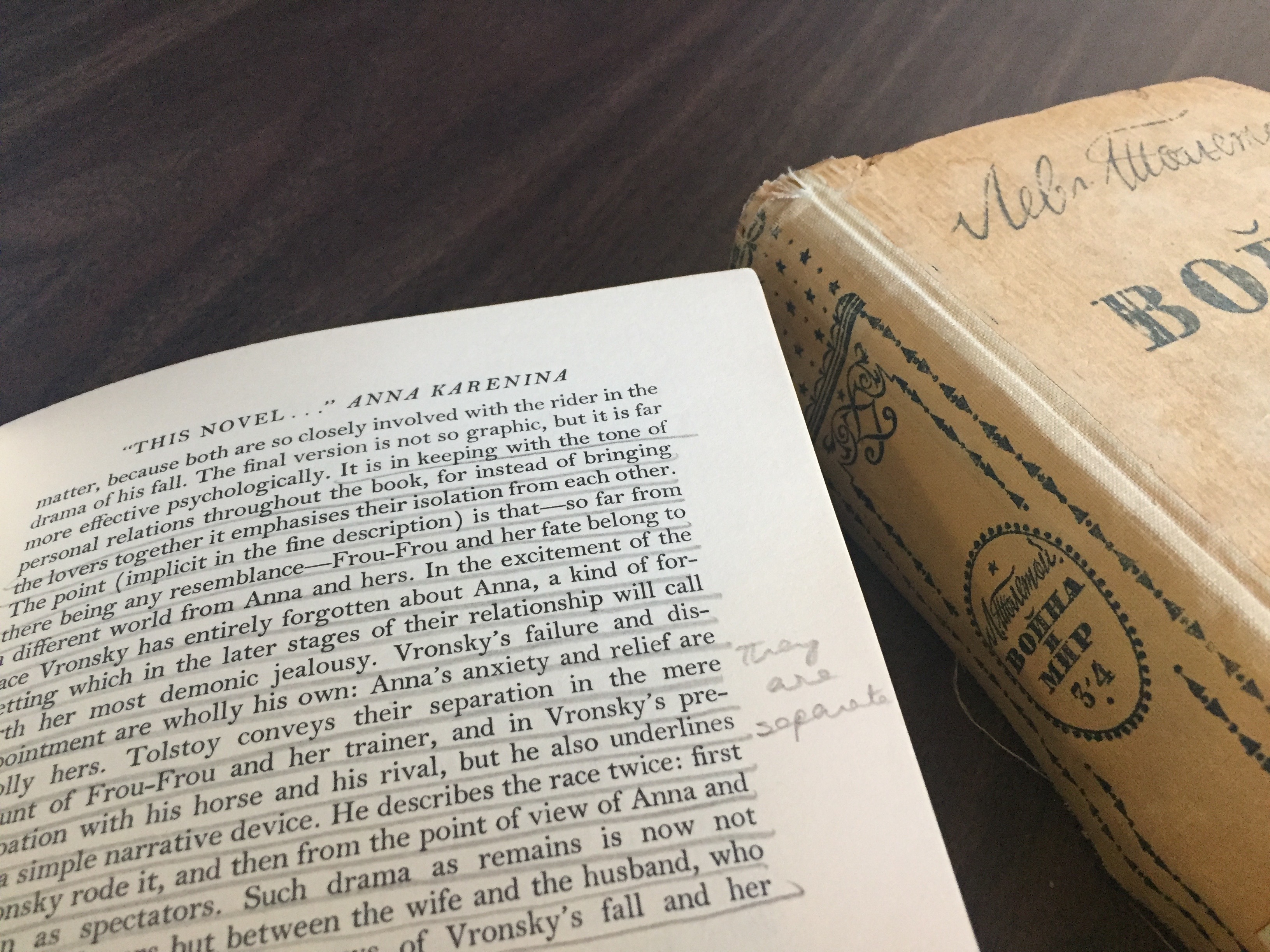

The homey sight of PS on a book’s spine—the Library of Congress’s code for American literature—draws me in. I love to feel durable pages worn soft from turning. Long rows of identical volumes from a set. Dulled gold to ornament a front cover. The best find of all is penciled notes in the margins. I’m not encouraging the vandalism of library books, of course, but I can’t deny the pleasure of seeing proof that someone else was once interested in the same thing I am.

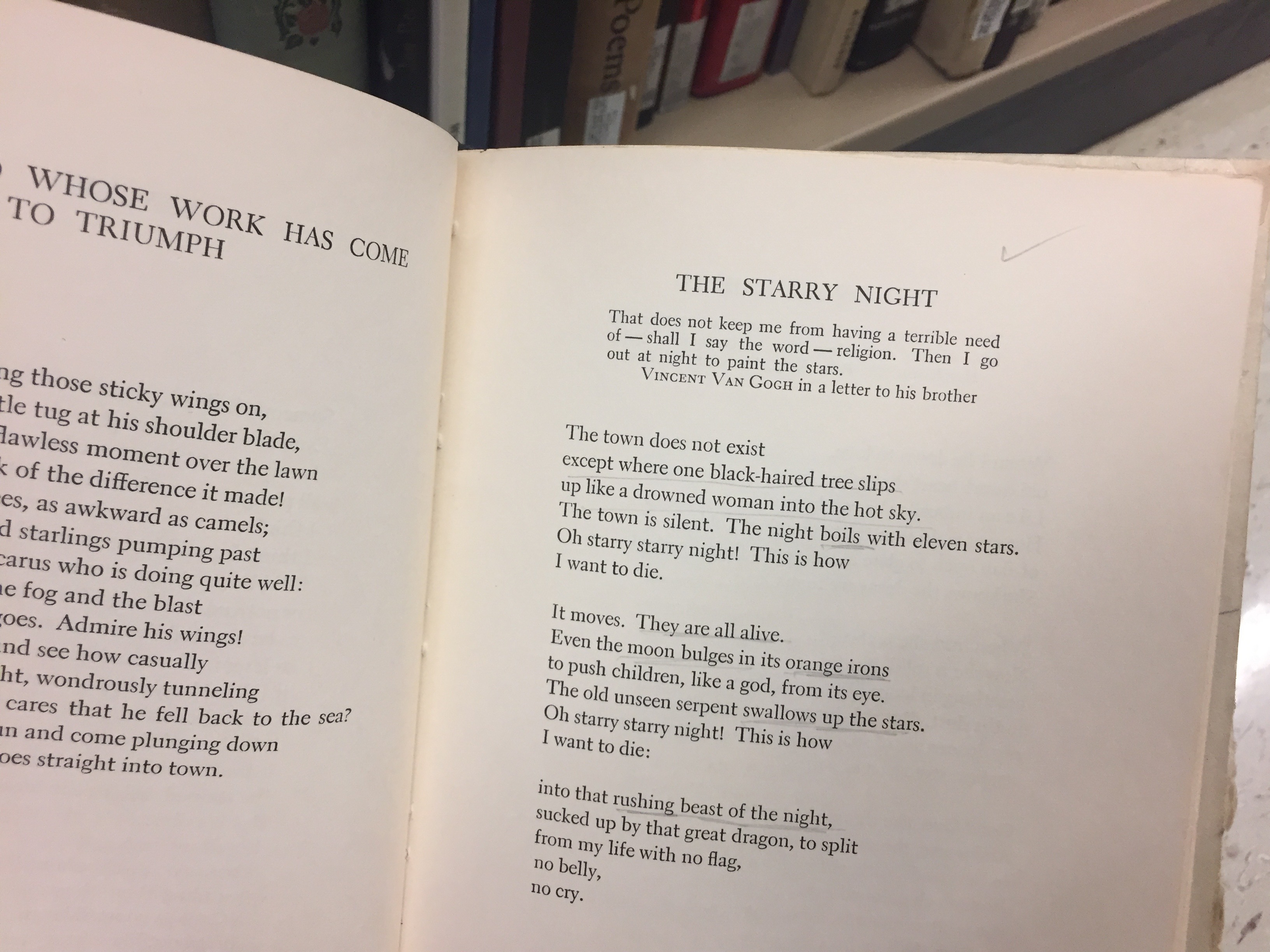

Just now, as I sat writing about library books, I remember that at the end of my first year at Bryn Mawr, I was working on a paper comparing Anne Sexton’s poem “The Starry Night” with Vincent van Gogh’s painting of the same name. I picture the Sexton book in my mind and remembered the annotations, so faint as to be nearly invisible. As I struggled to finish that poetry paper, the underlines and arrows reassured me I wasn’t just imagining the importance of my subject. I make my way back to the shelf where I’d left the book a year and a half ago, and there are the same pencil marks. It’s comforting. The unknown is a vast ocean, but every so often, academia can wrangle all that knowledge into a little curated pond of words remembered and treasured.