No matter how deeply you love Bryn Mawr’s campus, we all need to get away sometimes. During spring break I had some conversations with younger students that got me thinking about the barriers that prevent people from taking full advantage of our surroundings. The fact is, Bryn Mawr is a suburban school, and if you want to explore Philadelphia you either need to: own your own car, have a friend who has a car, be willing to spend a lot of money on Uber, or learn to use public transportation. Many people come from areas that do not have public transportation, and other people come from areas where the public transportation is different—read: easier to use—than it is here in Philadelphia. But I would encourage Bryn Mawr students to step out of their comfort zones and venture off campus.

I did not become fully comfortable using SEPTA (that’s Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, the general name for all modes of public transportation) until last summer, when I lived in Philadelphia for several months. Before then, I would hear people talking about the trolleys or subways, but I didn’t have the first idea of how to access these services. As I reach the end of my time at Bryn Mawr, I wanted to write a blog post that could be helpful for people who find themselves in the same boat.

PLANNING YOUR VISIT Visualizing Philadelphia:

Visualizing Philadelphia:

It’s easiest to start your Philadelphia adventures in Center City, which, as the name suggests, is the center of Philadelphia between the Schuylkill River to the west and the Delaware River to the east. The most important thing to remember is that Center City follows a grid system. Streets running north and south are numbered, and the numbers get higher as you go west. Streets running east and west have names. South of City Hall, many of these streets are named after trees such as Walnut and Chestnut. The only major exception is 14th Street, which is called Broad Street. City Hall is located at the intersection of Broad Street and Market Street. When I was first learning my way around, a friend advised me to stop every so often and get my bearings by asking myself where City Hall is, and then asking myself if I was facing north, south, east, or west. By doing this exercise frequently, I started to orient myself to the city and visualize myself on the grid.

Other neighborhoods:

You will probably hear people talking about neighborhoods like South Philly, University City, Fishtown, and many others. We don’t have enough space here to discuss every area of the city, and I am by no means an expert, but you can find fun things to do around the city by speaking with locals and researching online. This blog post will give you some tips later on to help you get from one place to another using public transportation.

In general, Google Maps is your best friend. As a very visual learner, I like to see a map before I visit a new place, and trace my route beforehand. Google Maps can also suggest other attractions nearby to where you are going that you might not have known about otherwise.

HOW TO GET TO THE CITY FROM BRYN MAWR

Bryn Mawr’s Regional Rail Station

Regional Rail:

The most common way for Bryn Mawr students to get into Philadelphia is through Regional Rail, which is a commuter train that takes about 25 to 30 minutes. Regional Rail stops at three stations in Center City. The closest one to Bryn Mawr is 30th Street Station, and many students don’t even realize there are two others. 30th Street is the most practical if you’re connecting to Amtrak, NJ Transit, Megabus or Bolt Bus; or if you are trying to get to West Philadelphia, the University of Philadelphia, or Drexel University. Otherwise, you’ll want to continue on to Suburban Station, which is next to City Hall. The third station is Jefferson Station, which is a couple blocks further east than Suburban.

The cost of a one-way Regional Rail ticket ranges from about five to seven dollars, depending on whether you get it in the Bryn Mawr station or on the train. If you go to the Bryn Mawr station (the little building next to the train tracks), you can pay with card or cash and receive a small discount, but it’s only open during very specific weekday hours. If you get a ticket on the train, you have to pay in cash and it will cost about a couple dollars more. It makes the most economic sense to buy an Independence Pass, which is a paper ticket that gives you unlimited access to any SEPTA services all day long. Even if you just plan on taking regional rail into Center City and then back to campus, an Independence Pass is a better deal than paying for a normal round-trip train ticket, so you should make sure to tell the conductor that’s what you want.

City Hall

Jefferson Station

The Norristown High Speed Line:

The NHSL is another way to get to Center City. It is cheaper but takes much longer. You have to walk about 20 minutes to Bryn Mawr Hospital and then board the NHSL, which is an above-ground train that costs $2.50. You ride the NHSL for about 10 minutes and get off at the last stop, which is the 69th Street Station. You then pay a $1 transfer fee and board the Market-Frankfort Line and ride that for about 15 minutes to Center City. I took this route twice a month this summer when I was visiting campus for beekeeping classes, because I could use my pre-paid monthly pass and thus save a significant amount of money. The trip can take upwards of an hour when you take into account transfer time, and I would personally say it is for advanced SEPTA passengers only.

HOW TO NAVIGATE ONCE YOU’RE THERE

SEPTA Key:

The SEPTA Key is a newer payment method modeled after services like New York’s MetroCard. I got a SEPTA Key Card this summer and would highly recommend it if you plan to take SEPTA frequently within Philadelphia. You pay $4.95 to get a plastic card, and then can refill it using a machine at pretty much any SEPTA station. You can get a Travel Wallet meaning you pay per ride (with a slight discount, paying $2 instead of the $2.50 you’d have to pay using cash), or you can get a weekly or monthly pass which offers an even greater discount but only is worth it if you’re going to be using SEPTA significantly during that period like if you have a job, internship, or are living in the city. The biggest downside of SEPTA Key is that it does not yet work on Regional Rail. The service is still in development, so hopefully future Bryn Mawr students will be able to take better advantage of it.

Edit: Thank you to SEPTA for reaching out with some additional information! They wrote, “The $4.95 cost is refunded in Travel Wallet funds if the card is registered within 30 days. Also, the $1 transfer is ONLY available with the Key card. Lastly they can also reload online at ”

Buses, trains, and trolleys:

The most annoying aspect of traveling from Bryn Mawr to the city is connecting between Regional Rail and other forms of transportation. Once you figure out this step, you can travel basically anywhere you want. Here’s a simplified run-down of the different types of transportation, and how to access them. All of these will cost around $2.00 per ride. You can still pay for the buses with cash, but the other forms of transportation require tickets bought in advance, such as an Independence Pass, or a SEPTA Key Card.

The Broad Street Line: This is a below-ground subway train that runs north/south along Broad Street. You can board the BSL at the City Hall Station, which you can enter underground after you get off Regional Rail.

Entrance to the Broad Street Line at Lombard Street

The Market–Frankford Line: This train, also called the El, goes east/west, partially underground and partially above-ground. It intersects with the BSL at City Hall, which on schedules of the MFL is often called 13th Street. I have found both the BSL and the MFL to be punctual. I can point to a few bad experiences when trains were extremely late or just never came, but these are the exceptions and not the rule.

Buses: The bus system is quite comprehensive, in my opinion, covering most of the city. I would recommend consulting Google Maps to choose the bus route that works for you. Like any city, you cannot always predict when exactly the buses will come, especially during non-rush hours, but they run more or less on time and consistently.

Hopping on the bus this summer

Trolley Lines: I have the least amount of experience with Philadelphia’s trolleys, but I have found them to be reliable and efficient. They tend to be most useful if you’re heading east/west, especially if you are going into West Philadelphia. They run underground like the trains but they have their own stations and entrances. Like the buses, I recommend using Google Maps to learn about trolley routes.

Waiting for the trolley

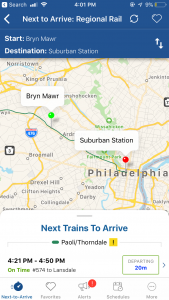

The SEPTA app:

SEPTA has an app! You can download it for free to check updated schedules for all services, see when the next train or bus will arrive, and get notifications on service delays. This app has been invaluable to me. It is intuitive and easy to use. As I wrote above, good old fashioned Google Maps is also excellent for navigating Philadelphia, and I have found that if you look up the directions to get somewhere using the “public transportation” feature,Google has accurate information that, if you’re taking a trip that requires connecting to multiple types of transportation, is easier to understand than the SEPTA app.

Concourses:

SEPTA’s underground concourse system deserves its own section just because of the amount of trouble it’s caused me. This interconnected warren of tunnels and caverns will confront you as you navigate the transportation in and around Center City. I probably got lost exiting the City Hall subway station my first twenty time going through it. And similarly, I spent an absurd amount of time this summer wandering around underground, after having descended at slightly the wrong corner, trying to find my platform. I’ll be the first to admit I have trouble visualizing spaces, but based on conversations I’ve had, this area tends to be confusing and overwhelming for many people.

I have two recommendations for confronting the concourse system: First, swallow your pride and ask SEPTA employees for help. Second, if you can’t locate an employee, don’t panic! I can’t even estimate how many times I unknowingly walked in circles underground, when I should have just taken a breath and come back up to street levels to get my bearings. I’m not trying to scare or discourage anyone—as long as you’re not on your way to an appointment, it’s fine to get a little lost. This is the time to explore and make mistakes. Everyone deserves that feeling of accomplishment that you get after learning your way around a new city, and in order to get there you’ll need to take some risks (safe and healthy risks, of course!). As a student, you have plenty of time to explore and get a little lost. I know it can be frustrating, but just try to think of this as an adventure.

DO I HAVE TO TAKE SEPTA?

If you just really don’t want to take public transportation you can also walk! If it’s a nice day I would recommend strolling east along Walnut or Pine Street, admiring the beautiful architecture and stopping anywhere that looks interesting. There are also many museums, theaters, restaurants, and other places to visit within walking distance of 30th Street Station or Suburban Station. Depending on how many steps you want to get in, you can go on foot to the historic sites around Independence Hall or down to Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens and South Street. Walking through the streets will help you feel more connected to the city and notice the small details.

Good luck! Feel free to reach out to me with any questions on this topic. I know firsthand how challenging it can be to move to a new city, and I would love to share my experience.

As participants settled into the sunny London Room for an embroidery workshop with artist-in-residence Gareth Brookes last week, the soft-spoken Londoner set us at ease with stories of how his mother taught him to embroider at the age of 4. He began by embroidering “boy things” like war scenes, but since then his work has developed into gorgeous and often haunting meditations on solitude, connection, and manifestations of home.

As participants settled into the sunny London Room for an embroidery workshop with artist-in-residence Gareth Brookes last week, the soft-spoken Londoner set us at ease with stories of how his mother taught him to embroider at the age of 4. He began by embroidering “boy things” like war scenes, but since then his work has developed into gorgeous and often haunting meditations on solitude, connection, and manifestations of home.

Field trips were one of the most exciting parts of my early school years. Getting to leave school during the middle of the day and bringing bagged lunches onto the bus were just the beginning of the adventure. Going to museums, theaters, and nature centers broke up our normal routine and got us learning in completely new ways. Field trips in college accomplish much the same function—and their infrequency makes them all the more novel.

Field trips were one of the most exciting parts of my early school years. Getting to leave school during the middle of the day and bringing bagged lunches onto the bus were just the beginning of the adventure. Going to museums, theaters, and nature centers broke up our normal routine and got us learning in completely new ways. Field trips in college accomplish much the same function—and their infrequency makes them all the more novel. Once we arrived at Taller, Velarde led us around the stunning exhibition, stopping to discuss the inspiration and thought-process behind each of the pieces. Her paintings are large-scale and impressive, incorporating a vast artistic language with influences ranging from 1940s pin-up style to the colonial Catholic tradition of the Cuzco School. Velarde told us, however, that she never starts a painting with the intention to communicate a political message. Rather, she focuses on the personal and aesthetic meaning of the piece. Nonetheless, political meaning seeps into her art, and despite the deeply individual subject matter, Velarde’s body often seems to act as a placeholder for larger communities.

Once we arrived at Taller, Velarde led us around the stunning exhibition, stopping to discuss the inspiration and thought-process behind each of the pieces. Her paintings are large-scale and impressive, incorporating a vast artistic language with influences ranging from 1940s pin-up style to the colonial Catholic tradition of the Cuzco School. Velarde told us, however, that she never starts a painting with the intention to communicate a political message. Rather, she focuses on the personal and aesthetic meaning of the piece. Nonetheless, political meaning seeps into her art, and despite the deeply individual subject matter, Velarde’s body often seems to act as a placeholder for larger communities. In “Hispanic Ready Made,” for example, Velarde depicts stereotypes of Latin American women superimposed onto her own body. The caricatured images, from a headpiece made of tropical fruits to sexualized outfits, mock the grotesque nature of stereotypes. Velarde said that she detests the word “Hispanic,” believing it to reflect a homogenization of diverse experiences. She would rather delve into the specifics of heritage and ethnicity, avoiding generalizations by referring to herself simply as Peruvian.

In “Hispanic Ready Made,” for example, Velarde depicts stereotypes of Latin American women superimposed onto her own body. The caricatured images, from a headpiece made of tropical fruits to sexualized outfits, mock the grotesque nature of stereotypes. Velarde said that she detests the word “Hispanic,” believing it to reflect a homogenization of diverse experiences. She would rather delve into the specifics of heritage and ethnicity, avoiding generalizations by referring to herself simply as Peruvian. Many of the paintings are depictions of a specifically female agony. “Love Me Diosito, Love Me” responds to what Velarde described as a cultural glorification of women’s suffering. “Yo Misma Soy” is an earlier self-portrait that shows Velarde exposed for the viewer’s inspection (Both of these can be found on Velarde’s website

Many of the paintings are depictions of a specifically female agony. “Love Me Diosito, Love Me” responds to what Velarde described as a cultural glorification of women’s suffering. “Yo Misma Soy” is an earlier self-portrait that shows Velarde exposed for the viewer’s inspection (Both of these can be found on Velarde’s website  “The Complicit Eye” is a gorgeous and haunting exhibit, and can be seen through April. Velarde is also constructing a mural, which we saw partially completed, and should be interesting to see again later on in the exhibition period. I was also disappointed by the difference between seeing the paintings in person and looking at the photos I took. I definitely was not able to capture their technical detail or precision, so I recommend taking a trip to Taller Puertorriqueño and seeing them yourself!

“The Complicit Eye” is a gorgeous and haunting exhibit, and can be seen through April. Velarde is also constructing a mural, which we saw partially completed, and should be interesting to see again later on in the exhibition period. I was also disappointed by the difference between seeing the paintings in person and looking at the photos I took. I definitely was not able to capture their technical detail or precision, so I recommend taking a trip to Taller Puertorriqueño and seeing them yourself! Visualizing Philadelphia:

Visualizing Philadelphia:

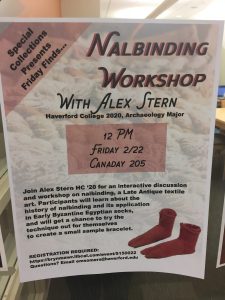

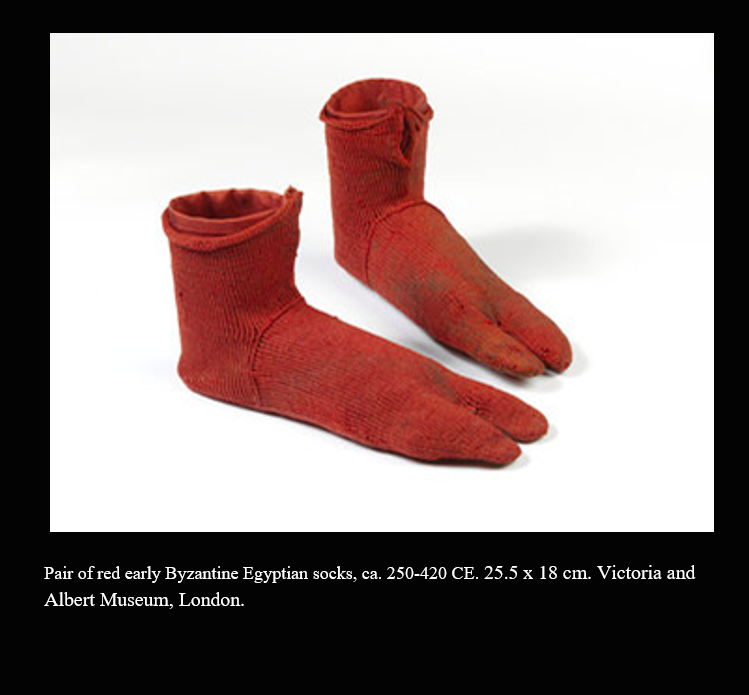

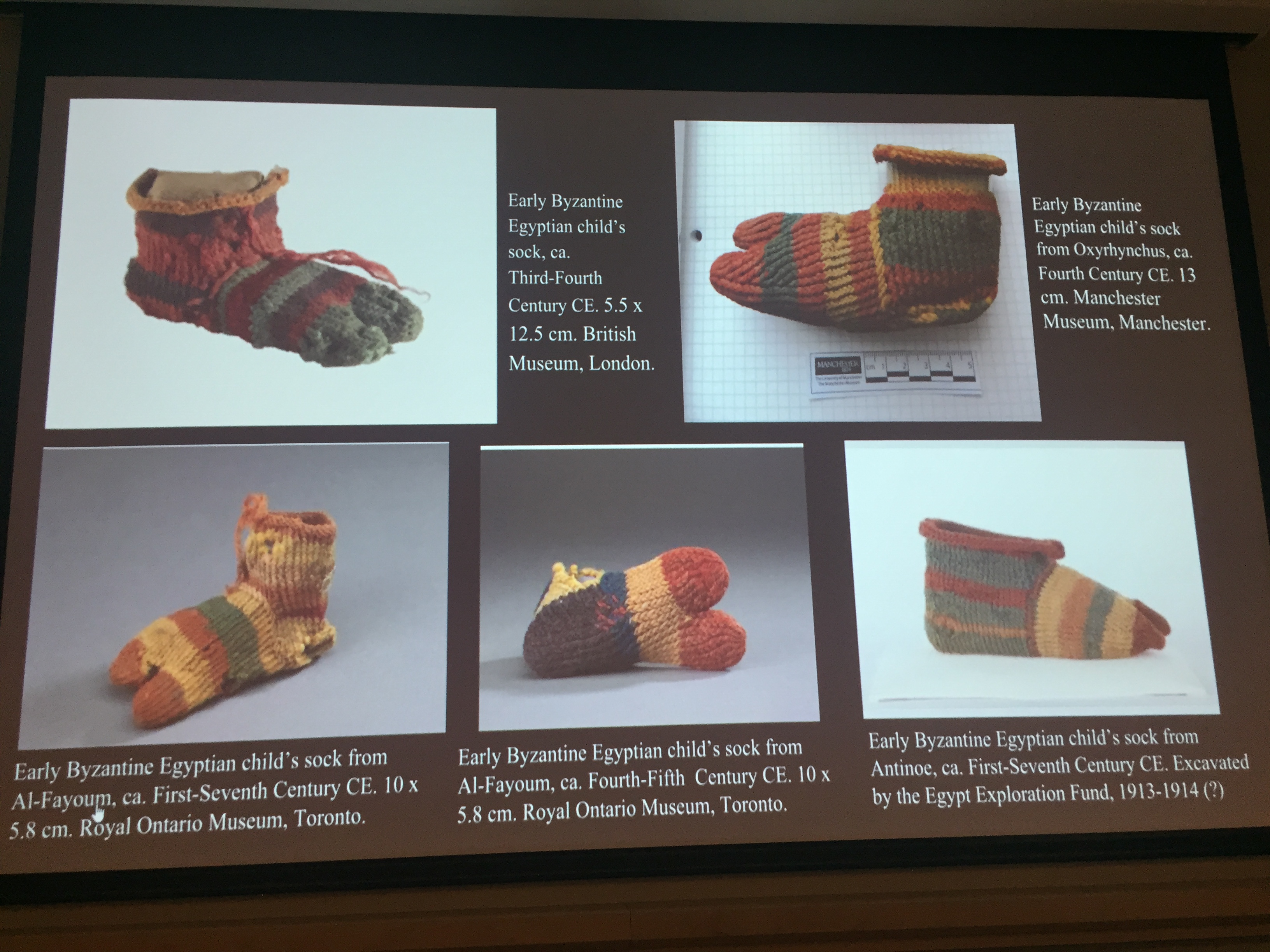

On a recent Friday I attended the latest event in Special Collection’s Friday Finds series. Alex Stern, a Haverford junior who is majoring in art history and archaeology at Bryn Mawr, facilitated a fun and fascinating workshop on nålbinding, an ancient weaving technique found in Byzantine Egypt.

On a recent Friday I attended the latest event in Special Collection’s Friday Finds series. Alex Stern, a Haverford junior who is majoring in art history and archaeology at Bryn Mawr, facilitated a fun and fascinating workshop on nålbinding, an ancient weaving technique found in Byzantine Egypt.

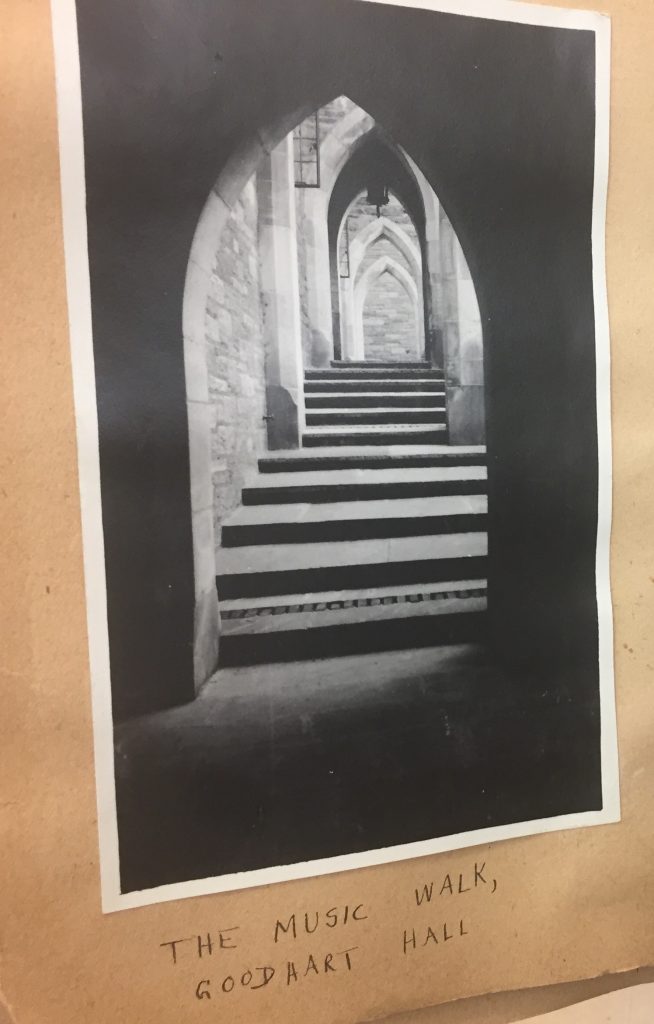

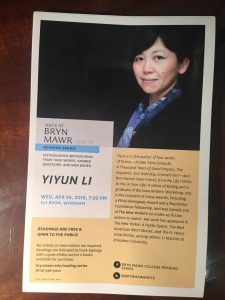

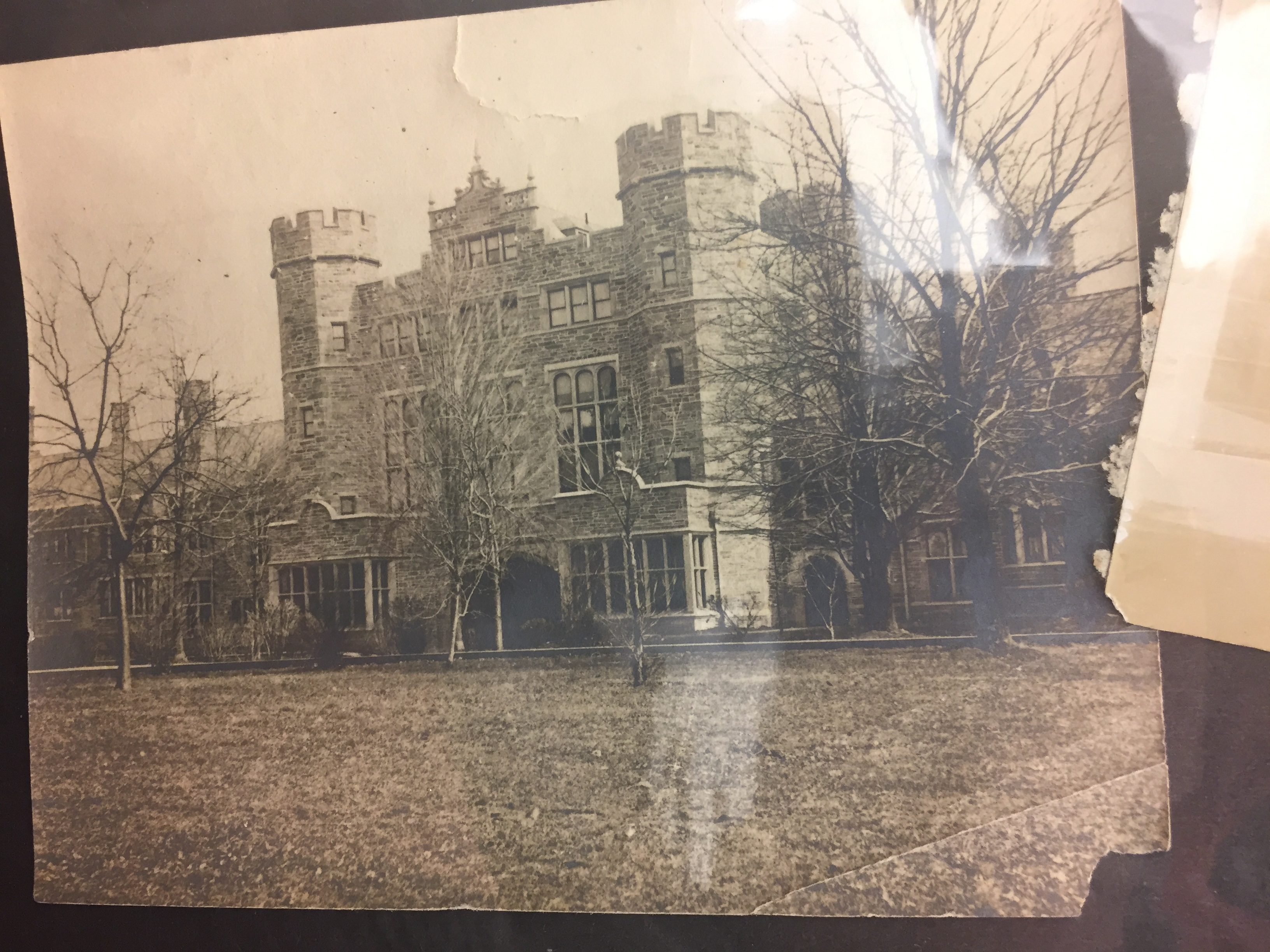

After attending an event co-hosted by Bryn Mawr College Hillel and Bryn Mawr Special Collections, I was thinking about the continuity of history, or lack thereof. Bryn Mawr’s historic architecture could be assumed to represent an unbroken lineage, lanterns passed down generation to generation without disruption. To the contrary, every new class recreates and reimagines our traditions. Not only do small aspects of the school’s culture shift over the decades—we no longer have class plays, for instance, as the student body has grown much too large—but our institutional values and mission develop as well. In Special Collections, I got to look at one of Thomas’s letters, in which she acquiesced to parents demanding their daughter be assigned a new roommate after finding out that her original roommate was Jewish, eventually leading to the policy of segregating Jewish students to particular housing.

After attending an event co-hosted by Bryn Mawr College Hillel and Bryn Mawr Special Collections, I was thinking about the continuity of history, or lack thereof. Bryn Mawr’s historic architecture could be assumed to represent an unbroken lineage, lanterns passed down generation to generation without disruption. To the contrary, every new class recreates and reimagines our traditions. Not only do small aspects of the school’s culture shift over the decades—we no longer have class plays, for instance, as the student body has grown much too large—but our institutional values and mission develop as well. In Special Collections, I got to look at one of Thomas’s letters, in which she acquiesced to parents demanding their daughter be assigned a new roommate after finding out that her original roommate was Jewish, eventually leading to the policy of segregating Jewish students to particular housing.